A Forgotten Wind: America’s Cold War Alliance with Somalia

As the Cold War drew to a close, the central authority of the Somali state crumbled due to the weakened health of President Siad Barre and the discontent at his violent and oppressive rule. The collapse of civil order led to widespread famine and misery among the civilian population. The dissolution of Somalia into warring factions mirrored the fate of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan around the same time. In 1992, the United States reacted to the deterioration of Somalia by organizing a UN mandated intervention, much as it had in the Persian Gulf from 1990–1991, and like the Persian Gulf intervention, the majority of the 37,000 personnel came from the United States.

What national interests did the Americans have in Somalia, a country largely unknown to the American public, that led to the deployment of 25,000 US troops to the African country? Various hypotheses were offered. Mark Fineman of the Los Angeles Times theorized that the intervention was staged for the benefit of oil corporations such as Conoco, Amoco, Chevron and Philips, who had received concessions from Siad Barre for exploration prior to his overthrow on January 26, 1991. But the concessions were located deep in the interior of the country, far from the presence of US troops. The value of the concessions was purely notional, and no infrastructure existed to exploit such deposits if they even existed.

Another hypothesis was that President Bush, having lost the 1992 election to Bill Clinton, was trying to uphold his legacy and leave office on a high note, particularly as he had been harshly criticized over his inaction in the former Yugoslavia. But the scale of intervention in a seemingly peripheral country appeared unnecessary to protect Bush’s legacy, particularly in light of the stunning military victory of Desert Storm, the reunification of Germany and the democratization of Eastern Europe, and the collapse of the USSR; if the latter was not precisely an achievement, it was certainly a favorable development.

A less obvious but more supportable argument was that the intervention followed an inertial trajectory of America’s previous strategic interests in Somalia, which dated back to the 1977 Ogaden War. Petroleum was indeed part of American interests in Somalia, but this had more to do with Somalia’s proximity to energy shipping routes than its own reserves.

The Horn of Africa: a Cold War Battlefield

In 1977, Somalia and Ethiopia were both ostensibly Marxist-Leninist states backed by the Soviet Union. But ideological similarities and a common patron could not overcome Somalia’s irredentist claims to the Ogaden region of Eastern Ethiopia, which was primarily inhabited by ethnic Somalis.

A bloody war from 1977–1978 ensued, with major geopolitical consequences. This internecine violence between ideological brethren in the late 1970’s mirrored patterns of conflict elsewhere in the world, namely the Cambodian-Vietnam war from 1978, the Chinese invasion of Vietnam in 1979, and the Khalq-Parcham rivalry within Afghanistan that culminated in the Soviet invasion of 1979.

Not only did the Soviets back Ethiopia against Somalia (the Ethiopians being regarded as Orthodox “brethren” since the days of Peter the Great), they helped organize a massive airlift of 13,000 Cuban soldiers and 1,500 Soviet advisors into Ethiopia. Between Soviet logistical support, Cuban fighting prowess, and the stubborn Ethiopian defense, the Somalis were driven out of Ogaden with heavy losses.

Once the Soviet tilt was apparent, but prior to the actual Cuban intervention, the Somalis expelled Soviet advisors and personnel from their country. After their defeat in the Ogaden conflict, Somalia became a US client state. From the end of the Ogaden war until Siad Barre’s fall, the US provided over $1 billion in military and economic assistance.

The Soviet-Cuban intervention came as a shock to the United States. Between the paralysis of will after Vietnam, and the entirely legitimate self-defensive actions of Ethiopia, the Americans could do little to to prevent such high profile power projection by the USSR. Zbigniew Brzezinski later said that “SALT lies buried in the sands of the Ogaden”, and along with it, Détente itself. Between the Ogaden War, the Iranian Revolution, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the Iran-Iraq war, the United States completely reorganized its strategic thinking towards Western Asia and Northern Africa.

This new outlook saw the birth of the Rapid Deployment Force, the precursor of CENTCOM, a military command designed to quickly deploy US forces to the Middle East (without compromising the defense of Western Europe or South Korea) in the event of a crisis in order to preserve the flow of oil from the Gulf. While the US had the necessary manpower and equipment, it had to create infrastructure in the region necessary to stage the buildup of personnel and material in the region.

American plans were greatly aided by Saudi cooperation. The Saudis invested some $100 billion into the US during the 1980s in exchange for military equipment and protection. In return, the US engineered a massive military infrastructure within the Kingdom, such as King Khalid Military City.

Meanwhile, the Camp David Accords bore fruit in the form of Egypt’s alliance with the United States and its recognition of Israel, a major setback for the USSR. Egypt and the United States initiated a series of military exercises known as “Bright Star”. Somalia factored into US strategic calculations as well. Its armed forces were invited to participate in the Bright Star exercises.

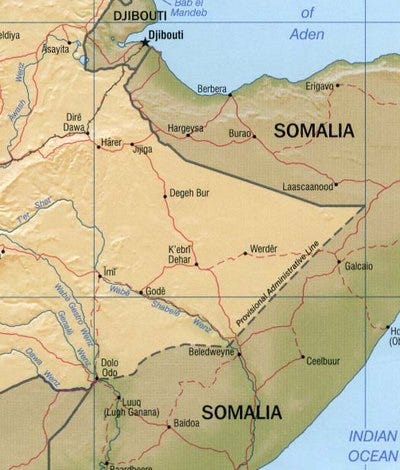

The Americans were particularly interested in the northern Somali port of Berbera. From a US perspective, Berbera was a highly strategic location. It was close to Bab-el-Mandeb, the Red Sea straits that connect the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and a major petroleum chokepoint. It was also directly across from the Soviet client state of South Yemen. Additionally, at 4km, the Soviet made airfield at Berbera was the longest airfield on the entire continent. As part of the Somali component of Bright Star, “Eastern Wind”, 2,800 US Marines and sailors of the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit, along with the USS Carl Vinson and USS Belleau Wood, deployed to Berbera in 1983.

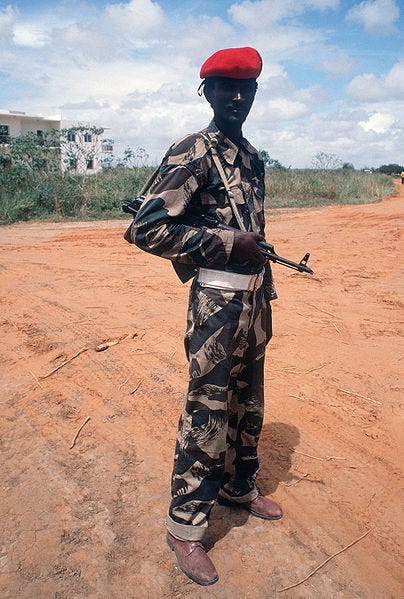

The Somali military was in shambles after the Ogaden debacle. Its participation in Bright Star did little to assure American observers that improvements had occurred. One diplomat observed that during Bright Star ’83, “the Somali army did not perform up to any standard.” In 1984, the Somalis accidentally fired on US F-15s conducting an exercise near Mogadishu. February 1985, the Somalis managed to shoot down one of their own aircraft. The Los Angeles Times described ineptitude of the Somali military as “legendary among foreign military men.”

The US began to lose interest Somalia as a partner. It feared rearmament of its new client state would encourage a new Ogaden adventure and it became increasingly apparent that the Somali military functioned as Barre’s personal enforcers rather than a national institution. More reliable logistical hubs had been established at Oman, Diego Garcia, and even Kenya. The Americans began to perceive their assistance to Somalia as more a means to keep the country from returning to the Soviet camp than consolidating itself as a reliable US ally. But American deployments did not cease altogether. The 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit deployed with the USS Guadalcanal to Geesalay, northeast of Berbera, in August 1987 while the US army trained the Somali 31st Commando Brigade as late as 1989.

Renewed Intervention: A Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

By 1988, the US-Somali relationship essentially broke down with the full scale eruption of civil war. The US had little incentive to support Barre as relations with the USSR improved and the importance of Somalia in US strategic thinking waned further. The Desert Storm campaign underscored Somalia’s irrelevance. The successful US military buildup in Saudi Arabia used infrastructure originally built up to react to Soviet or Iranian threats to the flow of Gulf oil. Barre was overthrown on January 26, 1991, as the US and its coalition allied were in the midst of an intensive air campaign against Iraqi forces. In other words, the scenario where Somalia might have played a strategic role had come to pass without any need for the country as a staging area. The Soviet dissolution at the year’s end removed the final rationale behind the US-Somali alliance. There was no longer a rival patron for Somalia to turn to, and as it was, there was no longer any central authority in Somalia to make such a decision.

Yet by the end of 1992, US forces had returned to Mogadishu in greater strength than ever. Declassified NSC documents reveal that while the Pentagon was initially reluctant to intervene, it came to believe that with international attention focused on Somalia and widespread support for UN action, that intervention would be inevitable. The logic ran that that the UN would be unable to cope with the rival militias and that a massive show of force by the United States would cow the recalcitrant factions. This policy ended with the corpses of US soldiers dragged through the streets of Mogadishu after the “Black Hawk Down” debacle.

Yet US involvement in Somalia persists to this day. After the the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the fragmentation of Somalia, like the fragmentation of Afghanistan, was perceived as a national security threat, particularly with the rise of Al-Qaeda aligned militias like the Islamic Courts Union and the even more extremist Al-Shabab movement. The danger to shipping lanes and the flow of oil returned, albeit not from the naval assets of a hostile power but by Somali piracy driven by poverty and desperation. Like the exhausted Afghan civilians did with the Taliban in 1996, Somali civilians welcomed the Islamic Courts Union’s control of Mogadishu in 2006 for bringing some semblance of order.

As of 2020, the United States remains heavily involved in Somalia. The civil war has even dragged in neighboring states like Ethiopia and Kenya, which in turn mired the US even further, since it needed to retaliate against Al-Shabab to maintain credibility withits African allies after the brutal Al-Shabab massacre of Kenyan civilians in the 2013 Westgate mall attack. Despite being the most culturally homogenous state in Africa, Somalia remains one of the most fragmented. Between clan factionalism, the secessionist Somaliland movement, and Al-Shabab, the central government controls less than a third of the country, despite support from the United States, Ethiopia, Kenya, and the African Union.

At the time of this writing, Al-Shabab actually collects more revenue than the central government, including from within Mogadishu itself, leaving the Somali government totally dependent on foreign financial assistance. So long as the government in Mogadishu requires external support for its continued existence, the United States will likely remain militarily involved in Somalia. In fact, an entirely new strategic dimension has emerged in the form of China’s presence in Africa, including its new military base in neighboring Djibouti.

Despite President Trump’s stated desire to withdraw all US forces from Somalia, further US military retrenchment in the country shows no sign of abating.